Artists such as Maya Lin exemplify the simplicity of such a structurally simple memorial. It has been described as a "scar" but it is incredibly simple, showing memorial without words. But what about using words or simple small objects to make a statement instead? This is where great figures in art such as Ai Weiwei come into place.

The sunflower seeds, backpack wall, and "Remembrance" audio recordings all show different ways to commemorate people, the common people. The sunflower seeds commemorate the importance of the individual in society no matter what social class, the backpacks point fingers at how the government ignores its lost children who had a potentially bright future, and the recording remembers those lost in tragedy. Each of these pieces ignores the traditional look of a memorial, being a statue or structure of permanence. Ai Weiwei's work uses temporary forms of media, the crushable seeds, perishable backpacks, and online readings to truly get his memorials to hit hard and fast, instead of being merely contemplative. Someone else, who, like Ai Weiwei is less of a fan of statue and more of a fan of direct words or impact is Lawrence Weiner.

All of Weiner's art, some of them seemingly meaningless, are different portrayals of words or phrases. The top picture is at the Greenway in Boston, his attempt to convey how "translation" of language and art into different styles of media help everyone connect with them. Something such as his simple phrases let everyone connect with his art and interpret it for his/herself. I definitely like the idea, and I picked these few for the specific reason that these are the ones I truly connected to. At first, I thought that the others were useless, meaningless phrases put up for no reason. However, I wonder if they connect to someone else the way these few connect to me.

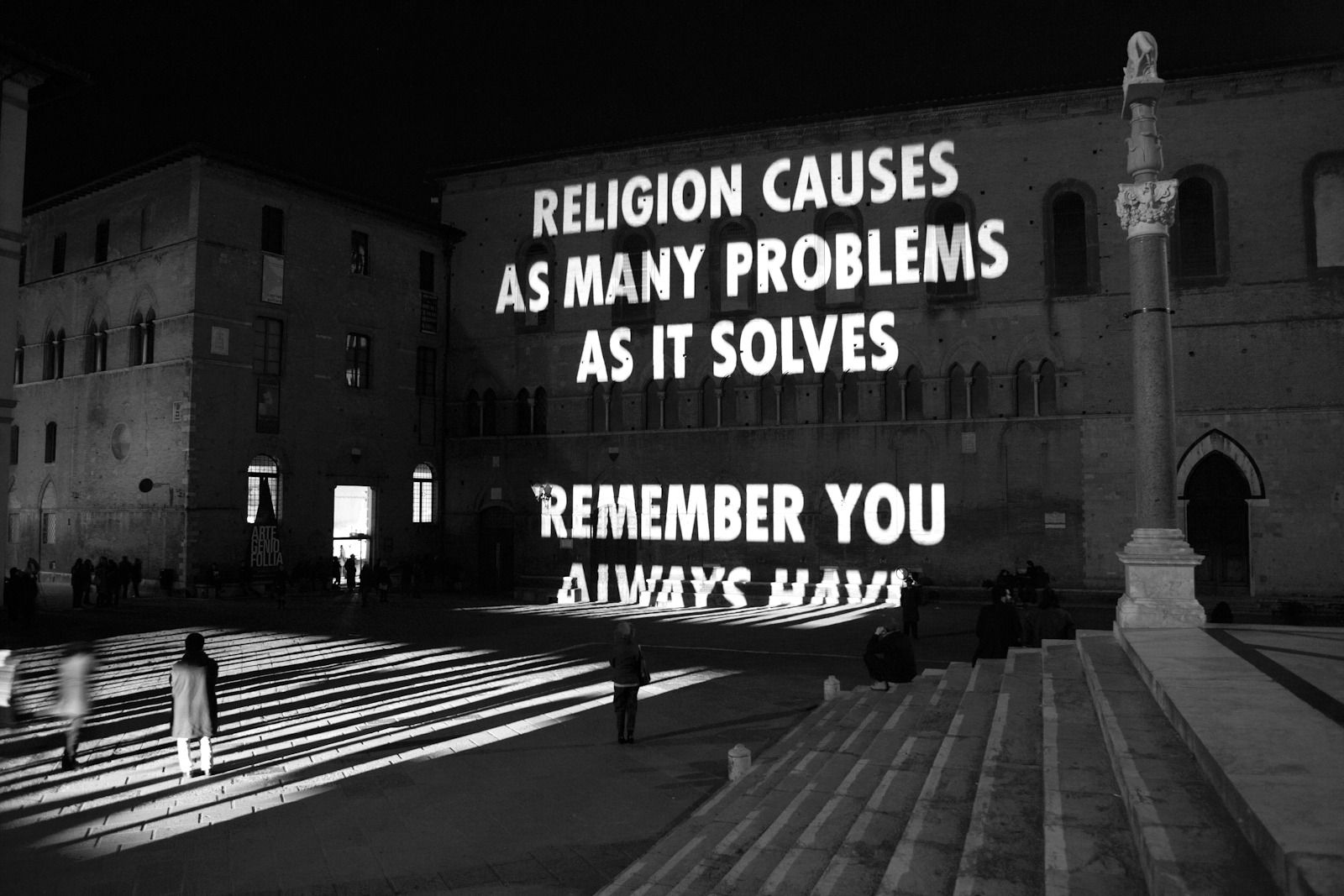

Another artist that uses words as a primary focus is Jenny Holzer, as well as Barbara Kruger.

Both of these artists use their words as the art, to convey a message or simply make a statement. While I wouldn't quite say that these pieces really act as a "memorial", they tell a story and make you think. I feel that this is truly at the core of art, that more flowery and "artistic" art is really just a statement at its core. Whether it is a statement as simple as "I think this scene is beautiful" or as complex as "we need to rethink society and its ideals", most art pieces have a skeleton phrase that gives the piece meaning. What Weiner, Kruger, and Holzer are doing is stripping the fluff and just painting or creating art of what they simply want to say, what point they want to make. In such a textual world, I think we as a society are more willing to accept such stripped bare pieces of art and appreciate their simplicity and directness.

Art such as that of Willie Cole,

Maya Lin,

and Ai Weiwei

all create pieces related to recycling. Cole's bottles send a message about recycling and how we use such an absurd amount of bottles and destroy the environment. Lin just uses old toys and milk cartons and repurposes them to be art, so as not to be wasteful and show the world what you can do with what you already have. Weiwei uses old relics and "destroys" them to challenge the perception of art and artifacts and their importance. Each of these artists is finding a new way to get their message across very simply, and at the core of all of these projects is a message that Weiner would stencil onto a wall or Holzer would project onto a hillside or Kruger would type in red and white and slap onto a monochromatic picture. As we come full circle, one realizes that at the core, whether art is a memorial of something, like Lin's commemoration of the Vietnam war and Weiwei's seeds, or a phrase, such as Weiner's murals and Holzer's projections, or even a recycled simplistic piece, such as Cole's bottles or Weiwei's vases, all art has the same idea. They are all simply trying to make a statement to the world, whether in obvious language or cryptic design.

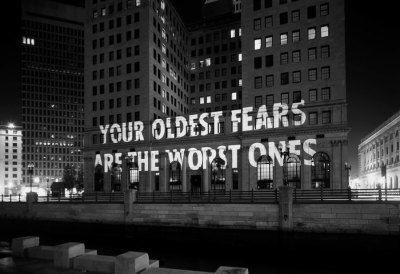

As a bonus and relevant to the last post, I saw this on my way to class today and went back later to take a picture:

I thought this was very interesting that this is still something advertised by those in charge in such a liberal-centric town.